UnityWorks: Baha’i-inspired training empowers Washington teachers and staff

Schools in the Yakima, Washington area face profound challenges. Located on the traditional homelands of the Yakama Nation, almost half of the population is White, and almost half is Hispanic, with a large immigrant population from Mexico, including many who speak only Spanish. Eighty-four percent of families live below the federal poverty line. Poverty, plus the legacy of social and educational discrimination, has led to homelessness, gangs as a substitute for family, and a “school-to-prison pipeline.” Students need much more than traditional education in such circumstances.

This is where UnityWorks helps. Its training model engages a team of administrators, teachers and staff from schools in a five-day summer training institute that includes singing, dancing, poetry, arts and crafts, and other activities that can be used in K-12 classrooms. Topics include race, gender, language, stereotyping, discipline, anti-bias curriculum and instruction.

The goal is to build capacity at the grassroots, empowering each team to create its own blueprint for change. On the final day of training, each team puts together a Diversity Action Plan aimed at reducing prejudice, promoting cross-cultural understanding, and giving students a firmer sense of belonging.

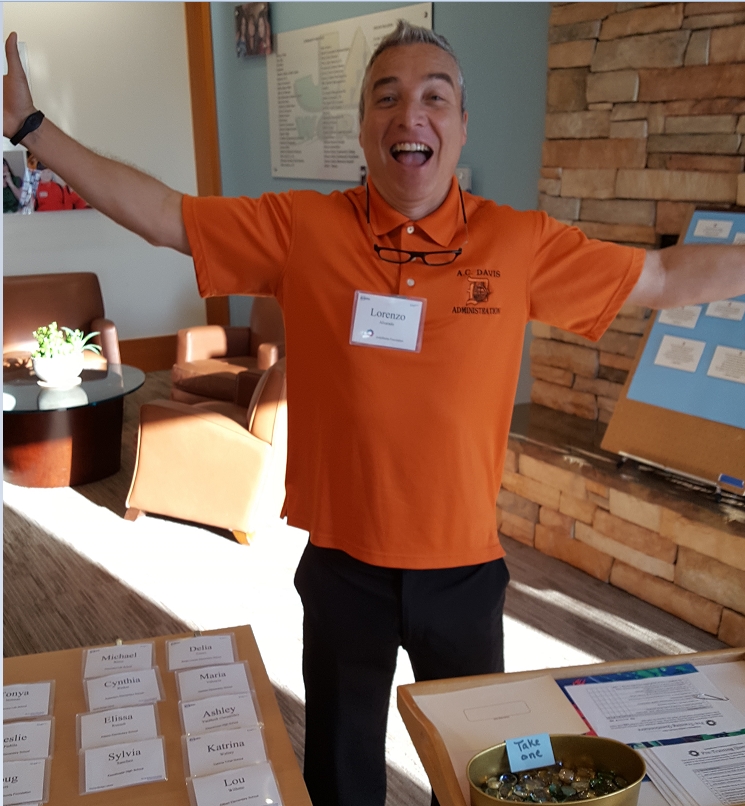

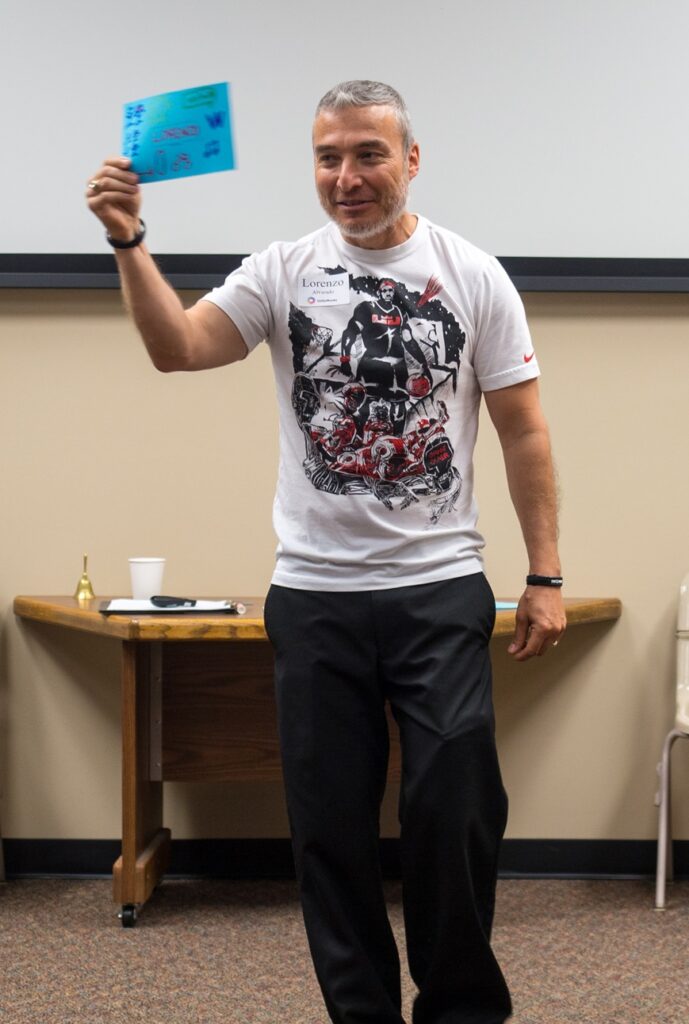

Lorenzo Alvarado has seen this play out at the high school where he serves as Assistant Principal. In a workshop at the National Race Amity Conference last November, he reported that in cases where activities inspired by UnityWorks take root, “The kids are proud of where they come from. They’re happier at school and they do better academically.”

Alvarado, a board member for UnityWorks, and Randie Gottlieb, the organization’s founder and director, offered the workshop at the conference in Atlanta on Nov. 10 to help acquaint people with the program’s aims and methods.

Starting with one school in Yakima in 2014, UnityWorks grew to serve 26 schools across Washington state before COVID-19 interrupted in-person training. It has since expanded to online training nationwide, thanks to capacities developed during the pandemic.

Gottlieb, a longtime Baha’i who taught graduate multicultural education courses at the local university for more than a dozen years before UnityWorks was established, points out that diversity in schools is not an ideal or an aspiration — it’s a fact.

Nationwide, the population of color has grown to include more than half of all public-school students, and is expected to encompass half the total U.S. population by the 2040s. She notes that public schools in Kent, Washington, for example, have students from over 138 language backgrounds.

As culturally rich as this may be, she says, it presents challenges for learning. “Many children, for example, already hold negative stereotypes of other racial groups by the time they enter first grade.”

Bearing this reality in mind, Alvarado says a key starting point for UnityWorks’ operation is “helping educators to recognize the oneness of humankind. That is the firmest basis for building relationships that can be safe places for healing.”

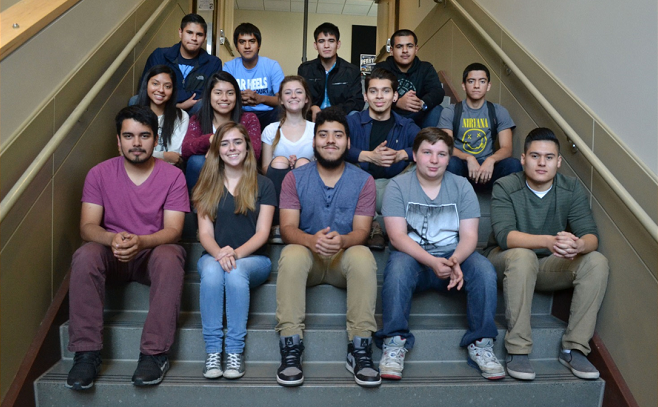

He shares an example of those principles in practice. One high school developed monthly lessons on prejudice, stereotyping, race and culture for all students. It also hosted an international students’ cultural fair, with much of the planning entrusted to the students themselves. They were excited to share their culture’s history, geography, languages, foods and other elements.

At another high school, the UnityWorks team organized a well-attended exhibit on African-American history ― one of the missing chapters in their textbooks. The school also formed a student multicultural club dedicated to learning and service.

One middle school was concerned with the lack of parental involvement, which correlates with low academic achievement, so they set the goal of increasing community participation. In consultation with local families, they decided to do this by learning about the cultures represented in their school, with teams of staff, students and parents meeting monthly to prepare a year-end cultural celebration. The plan was a success, with participation growing from only five parents at the start of the year, to more than 450 at their culminating activity.

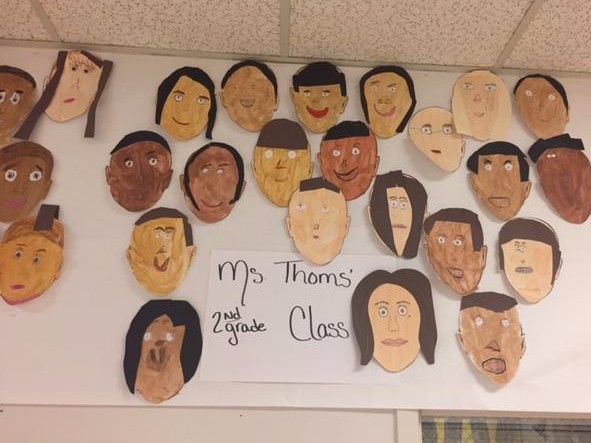

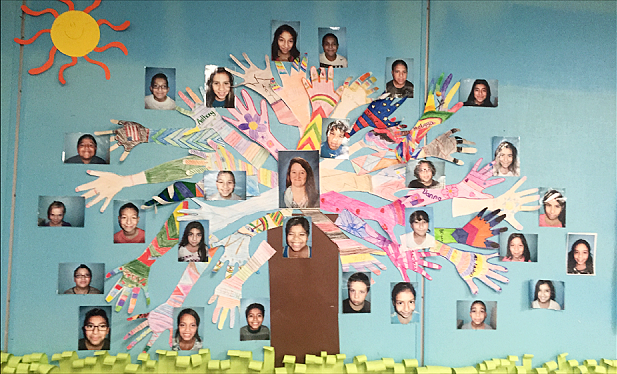

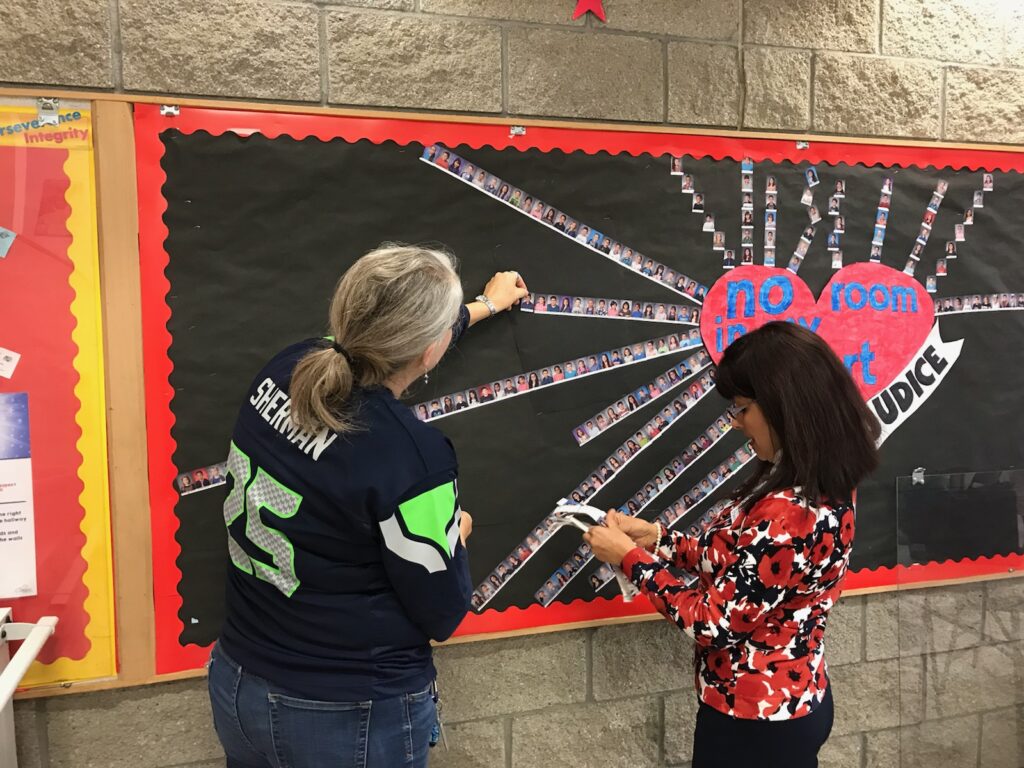

Cooperative projects at elementary schools had students working together to explore themes such as “No Room in My Heart for Prejudice”; virtually visiting each other’s ancestral countries with a “magic school bus”; and more. As part of a science lesson, one teacher created a family tree to show that, although there are many branches, we are all leaves of one tree. At another school, a series of artistic lessons on race and skin color helped quell a sharp increase in racial bullying, Alvarado said.

The workshop offered testimonials from administrators and educators who have gone through the UnityWorks training. “I came in here with an intellectual lens. Through the experiences this week, it’s gone from my brain to my heart,” said a school counselor. “Even though I’m young, I can make a difference. Others say I can’t, but I can!” said a high school student who took part in a training. “It’s a way of validating every student we serve, whatever their ethnicity or upbringing may be,” said a teacher who has worked with the program at her elementary school.

The presenters also mentioned some tools they have developed to support these diversity, equity and inclusion efforts, including a “Teaching Unity” curriculum guide, a PDF handout on “Overcoming Prejudice,” colorful PowerPoint shows for kids, constructive conversation guides, assessment tools, and classroom art.

And Gottlieb reaffirmed that the oneness of humanity remains at the center of this effort. “Each one of us has this challenge,” she said: “to expand the circle of who you call ‘us.’”