The Master of Akka

History of Master’s Life

The Master of Akka

Source:Myron Henry Phelps and Bahiyyih Khanum, Life and Teachings of Abbas Effendi

Bahiyyih Khanum wrote about her brother, ‘Abdu’l-Baha:

SMALL as this world is, boast as we may of our means of communication, how little we really know of other lands; how slowly the actual thoughts, hopes, and aspirations of other peoples, the deep and real things of their lives, reach us, if they indeed ever reach us at all!

SMALL as this world is, boast as we may of our means of communication, how little we really know of other lands; how slowly the actual thoughts, hopes, and aspirations of other peoples, the deep and real things of their lives, reach us, if they indeed ever reach us at all!

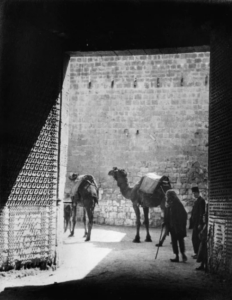

Imagine that we are in the ancient house of the still more ancient city of Akka, which was for a month my home. The room in which we are faces the opposite wall of a narrow paved street, which an active man might clear at a single bound. Above is the bright sun of Palestine; to the right a glimpse of the old sea-wall and the blue Mediterranean. As we sit we hear a singular sound rising from the pavement, thirty feet below – faint at first, and increasing. It is like the murmur of human voices. We open the window and look down. We see a crowd of human beings with patched and tattered garments. Let us descend to the street and see who these are.

It is a noteworthy gathering. Many of these men are blind; many more are pale, emaciated, or aged. Some are on crutches; some are so feeble that they can barely walk. Most of the women are closely veiled, but enough are uncovered to cause us well to believe that, if the veils were lifted, more pain and misery would be seen. Some of them carry babes with pinched and sallow faces. There are perhaps a hundred in this gathering, and besides, many children. They are of all the races one meets in these streets – Syrians, Arabs, Ethiopians, and many others.

He stations himself at a narrow angle of the street and motions to the people to come towards him. They crowd up a little too insistently. He pushes them gently back and lets them pass him one by one. As they come they hold their hands extended. In each open palm he places some small coins. He knows them all. He caresses them with his hand on the face, on the shoulders, on the head. Some he stops and questions. …As they pass, some kiss his hand. To all he says, “Marhabbah, marhabbah” – “Well done, well done!”

On feast days he visits the poor at their homes. He chats with them, inquires into their health and comfort, mentions by name those who are absent, and leaves gifts for all.

Nor is it the beggars only that he remembers. Those respectable poor who cannot beg, but must suffer in silence – those whose daily labor will not support their families – to these he sends bread secretly. His left hand knoweth not what his right hand doeth.

All the people know him and love him – the rich and the poor, the young and the old – even the babe leaping in its mother’s arms. If he hears of any one sick in the city – Moslem or Christian, or of any other sect, it matters not – he is each day at their bedside, or sends a trusty messenger. If a physician is needed, and the patient poor, he brings or sends one, and also the necessary medicine. …

This man who gives so freely must be rich, you think? No, far otherwise. Once his family was the wealthiest in all Persia. But this friend of the lowly, like the Galilean, has been oppressed by the great. For fifty years he and his family have been exiles and prisoners. Their property has been confiscated and wasted, and but little has been left to him. Now that he has not much he must spend little for himself that he may give more to the poor. His garments are usually of cotton, and the cheapest that can be bought. Often his friends in Persia – for this man is indeed rich in friends, thousands and tens of thousands who would eagerly lay down their lives at his word – send him costly garments. These he wears once, out of respect for the sender; then he gives them away.

This man who gives so freely must be rich, you think? No, far otherwise. Once his family was the wealthiest in all Persia. But this friend of the lowly, like the Galilean, has been oppressed by the great. For fifty years he and his family have been exiles and prisoners. Their property has been confiscated and wasted, and but little has been left to him. Now that he has not much he must spend little for himself that he may give more to the poor. His garments are usually of cotton, and the cheapest that can be bought. Often his friends in Persia – for this man is indeed rich in friends, thousands and tens of thousands who would eagerly lay down their lives at his word – send him costly garments. These he wears once, out of respect for the sender; then he gives them away.

He does not permit his family to have luxuries. He himself eats but once a day, and then bread, olives, and cheese suffice him.

His room is small and bare, with only a matting on the stone floor. His habit is to sleep upon this floor. Not long ago a friend, thinking that this must be hard for a man of advancing years, presented him with a bed fitted with springs and mattress. So these stand in his room also, but are rarely used. “For how,” he says, “can I bear to sleep in luxury when so many of the poor have not even shelter?” So he lies upon the floor and covers himself only with his cloak.

For more than thirty-four years this man has been a prisoner at Akka. But his jailors have become his friends. The Governor of the city, the Commander of the Army Corps, respect and honour him as though he were their brother. No man’s opinion or recommendation has greater weight with them. He is the beloved of all the city, high and low.