Race awareness gatherings benefit from Illinois woman’s family quest

By Christopher Carpenter

As a child growing up in Chicago’s northern suburbs in the 1940s and ‘50s, Judy Hughes was familiar with the Baha’i House of Worship in Wilmette, Illinois. Her father used it as a landmark during flights over Lake Michigan as a Navy pilot stationed in Glenview and he took Hughes and her sister to visit the Temple.

Later, while raising her family in Northbrook, Hughes met Baha’is while helping to organize a tour of the town’s places of worship and again when she became involved in an organization called RAIN (Racial Awareness in the North Shore), established in 2015.

After the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020, she deepened her involvement in Baha’i activities. Hughes says Baha’i beliefs and the work of the Faith to bring about race amity mirror the values that have guided her life.

She joined a local devotional gathering in Northbrook called “Searching for my role in building race amity.” She also attends and was a featured speaker at another Bahá’í-inspired gathering, “An intimate dialogue on race.” This online gathering starts with various holy scriptures.

“I am drawn to spending time with like-minded people,” Hughes says of her recent involvement, “and the fact that these group interactions provide a space for open dialog and the opportunity to work together to bring about awareness and change.”

Hughes, who is white, brings to Baha’i gatherings a commitment to racial justice and a unique story about connecting with African Americans whose ancestors were enslaved by her own ancestors in North Carolina.

On a visit to Davidson, North Carolina, in 1983, she was searching for family gravesites when she passed a store that had “Withers” in the name and stopped to talk to the owner because she had ancestors by that name. She found that she and the owner were distantly related. He shared a box of family memorabilia that included a family Bible containing the names and, in some cases, birthdates of 34 people enslaved by Hughes’s family. Written in pencil above several of the younger ones’ names were the names of their mothers.

Given that before 1870, the names of African Americans were often not included in the census, Hughes knew this Bible would be considered a treasure trove of information for some African American families.

“I made a promise to myself that someday or somehow I would find the descendants of some of these people and pass that information down,” Hughes says.

Hughes returned to Illinois with pictures of the Bible and other records and devoted what time she could to the task while also serving on the school board and working for various community organizations, including the local historical society.

She joined Ancestry.com in 2000 to help her in her search and took a DNA test in 2012 to find additional connections. In 2015 she joined a Facebook group called “I have traced my enslaved ancestors and their owners” where, in 2018, she saw a post by an African-American woman in Georgia named Michele Johnson explaining that Johnson’s great-great-grandfather was the offspring of a white man named Withers in North Carolina. No one in Johnson’s family knew the man’s identity, and she asked for help tracking down information.

Hughes responded within minutes, and she and Johnson talked on the phone the next day.

“For me, it was a dream come true,” Hughes says, “but it was also a moment of, ‘What do I say? How can I say I’m sorry? How can I convey that this is important to me?’”

Johnson says she could hear tears in Hughes’s voice during the phone call, which was emotional for her as well, but for a different reason.

“My mother was the one who did all of our family research,” Johnson says, “and one of her dying wishes for me was to continue her research. So, for me it was emotional because I wished it was my mom talking to Judy. I wish that she had been the one to take that call, because I know how much it meant to her to solve that mystery.”

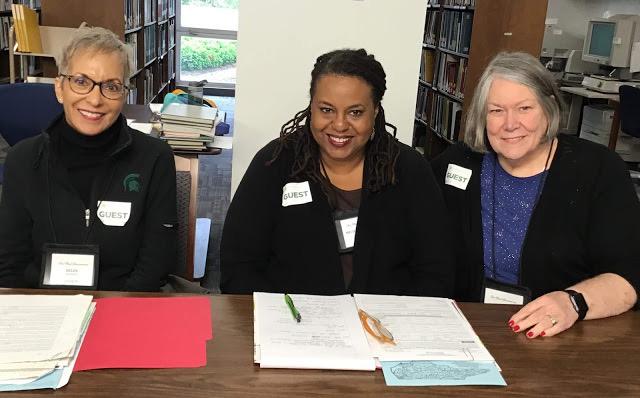

state archives conducting family research.

Hughes and Johnson, who is also a family genealogist, began sharing resources and pooling their efforts. A broader picture of both of their families and the ways they were connected began to emerge. Going back six generations, Hughes found a connection to a woman named Helen Mickens, who traces her lineage to one of the enslaved women listed in Hughes’s Bible and with whom Hughes shares a common white ancestor.

Mickens and Hughes met in person in the fall of 2018 and decided to spend a week together searching for additional information at the North Carolina Archives, where Johnson also joined them for a day. Their circle has now expanded to about 12 people—both Black and white—who are all connected by DNA.

“I’ve learned so much about slavery from doing genealogy,” Johnson says. “When you learn about slavery in school you hear that we were brought here from Africa, we were enslaved, and that’s pretty much it. When you do genealogy, you realize how one family member would leave slaves in a will for someone else. People were passed down literally like property.

“We’ve all been kind of tracking those transactions within our family, finding out how we’re related, and searching for some of that information that we’re missing,” Johnson says.

Hughes feels a deep family connection to her discovered cousins. She and Mickens belong to a book club started by Johnson, and the three women have shared their story of connecting in a number of venues. Johnson says she doesn’t hold Hughes responsible for what her ancestors did and appreciates that Hughes and the other members of the group all genuinely want to find information about their families.

“We’re all close, even though some of us have never met face-to-face,” Johnson says. “We all have a deep respect and, I would say, love for each other.”

For Hughes, the connection has deepened her empathy for African Americans who experience racism. When Ahmaud Arbery was killed while jogging through a white neighborhood in Georgia, Hughes sent Johnson a message saying how sorry she was and promising that she would not remain silent about the killing. Johnson responded by saying that her son grew up with Arbury and that the two had been classmates since childhood.

“I know that the pain I was feeling was a surface pain,” Hughes says, “a pain that everybody who wants justice was feeling. But what she [Johnson] was feeling—what now a member of my family was feeling—was a whole different feeling.”

Hughes says, “The best way to describe it is the difference between the shock and sadness you feel about the sudden death of an acquaintance and the visceral reaction and depth of your feelings when it happens to a family member.”

Another African American member of the group named Tony Harris shared his experience of being in a store with his wife and seeing a white man covered in personal protective equipment that included a complete suit, a mask and a baseball cap pulled low over his face; the man also wore a pistol on his hip in plain view, which is legal in the state where they live.

“Tony’s remark was, ‘If that had been me dressed up like that, I would have been shot,’” Hughes says. “I know that [intellectually], but I had another visceral reaction because it was my family that we were now talking about, my group.”

Hughes shared her experiences with others in the weekly devotional she attends in Northbrook, which includes people of Black, Hispanic, Persian and white backgrounds. Her stories, along with those of others in the group, help to raise awareness and encourage self-reflection.

The devotional group, which meets on Sunday evenings, begins each meeting with music and prayers, followed by discussion and planning for action. Its members planted the seeds that, in June 2021, grew into Northbrook’s first Race Amity Day celebration, in which Hughes played a central role. The group is already planning a second Race Amity Day.

Van Gilmer, an African American Baha’i who coordinates the “Intimate Dialogue on Race” in which Hughes, Johnson, and Mickens shared their stories of connecting through genealogy, says Hughes offers an example people can learn from.

“She genuinely wants to make a difference in race awareness,” Gilmer says. “[Talk] is not what her goal is. She has even found her relatives who are Black.”

Mary Hansen, a Baha’i who has been in the Northbrook devotional group with Hughes for more than a year, echoes Gilmer’s sentiment. She says she appreciates Hughes’s example of connecting with her cousins and working against racism in her local community.

“She has an ability to think, ‘What’s the local angle about this? What is going to engage the local people on this particular topic that I’m very interested in?’” Hansen says.

Hughes hopes her efforts to make her community more equitable and inclusive—both in Bahá’í circles and in the wider society—will make a small but meaningful difference.

“You throw a pebble in the pond, and we have a circle, and that intersects with the next circle,” Hughes says. “Hopefully, pretty soon the waves will join together and make the changes that I have wanted all my life.”