Integrating Meetings

Race-Unity-Justice

Integrating Meetings

Source: Abdu’l-Bahá in America: The Diary of Agnes Parsons

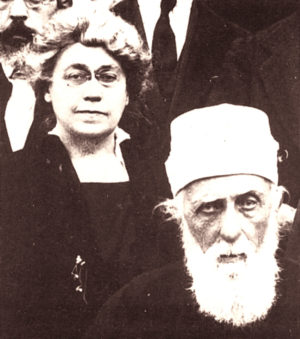

Mrs. Parsons wrote in her diary, Washington, D.C. was home to the most diverse Baha’i community in North America: it had within its fold the largest group of African-Americans, and virtually all social classes, from the working poor to the social elite, were represented in it. As part of the American south, Washington, D.C. was also a city in which racial segregation was a fact of life, and it was on the issue of racial equality that `Abdu’l-Baha was most uncompromising during his visit to America. On one occasion, which is mentioned briefly in this diary,`Abdu’l-Baha shocked some of the white socialites present by insisting that Louis Gregory, an African-American Baha’i and lawyer, be seated next to him at a society luncheon. In such a milieu, the Baha’is found it challenging to comply with `Abdu’l-Baha’s instruction that they should hold racially-integrated meetings. Even locating a public site for a community dinner honoring`Abdu’l-Baha proved difficult, since no hotels in the city would allow an integrated meeting.

Mrs. Parsons wrote in her diary, Washington, D.C. was home to the most diverse Baha’i community in North America: it had within its fold the largest group of African-Americans, and virtually all social classes, from the working poor to the social elite, were represented in it. As part of the American south, Washington, D.C. was also a city in which racial segregation was a fact of life, and it was on the issue of racial equality that `Abdu’l-Baha was most uncompromising during his visit to America. On one occasion, which is mentioned briefly in this diary,`Abdu’l-Baha shocked some of the white socialites present by insisting that Louis Gregory, an African-American Baha’i and lawyer, be seated next to him at a society luncheon. In such a milieu, the Baha’is found it challenging to comply with `Abdu’l-Baha’s instruction that they should hold racially-integrated meetings. Even locating a public site for a community dinner honoring`Abdu’l-Baha proved difficult, since no hotels in the city would allow an integrated meeting.

Beneath the concern of Washington’s upper classes to uphold long-standing social conventions regarding racial segregation were deep-rooted prejudices not easily overcome. Even Mrs. Parsons’ husband once commented to `Abdu’l-Baha that he wished all the blacks would return to Africa, to which the Master wryly replied that such an exodus would have to begin with Wilber, the trusted butler of the Parsons household. While Mrs. Parsons herself would not have harbored such sentiments, having accepted the Baha’i teaching on the oneness of humanity, her social position would have made it extremely difficult for her to accept African-Americans as persons with whom she could have social relations as equals, and it may also have made her reluctant to advocate racial integration, even within the Baha’i community.

On this subject, the silences of this diary are perhaps more telling than what is recorded. For example, there is scarcely a mention of any of `Abdu’l-Baha’s talks at the homes of Andrew Dyer and Joseph Hannen, both of which were sites of racially integrated meetings for the Washington, D.C. Bahá’í community, or at African-American venues, such as the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church, presumably because Mrs. Parsons did not attend most of these events. Such activities were not part of the social world in which she lived. It is remarkable, then, that `Abdu’l-Baha subsequently chose Agnes Parsons to spearhead the Racial Amity campaign initiated by the Baha’i community and as remarkable that she transcended her social milieu in order to carry out this mandate.

__________________________________

The first Race Amity Conference in 1921 was held based on instructions directly from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Agnes Parsons, a prominent DC socialite, had visited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Palestine in 1910 and, when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá came stateside in 1912, he stayed at her home in Washington, DC.

In 1920 Parsons again visited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Palestine, and at that time he asked her directly to arrange a convention promoting harmony among all races. She began collaborating with other Bahá’ís like lawyer Louis Gregory and professor Coralie Cook, and invited the participation of many like-minded organizations. That first Race Amity Conference drew more than two thousand people for a program that included poetry, singing, talks from political leaders, and more.

Read more about Race Amity here: https://www.bahai.us/ncra-to-celebrate-century-long-legacy-of-promoting-race-amity/