Children’s spiritual education in Oregon inspires evolution in thought, action

Baha’i children’s classes are being offered to an ever-widening circle of families in the Greenway neighborhood of Beaverton, Oregon. Some of those families have grown closer as they gather regularly to support each other in prayer, study and service.

For at least one Baha’i, the experience has reaffirmed a basic teaching of the Baha’i Faith: that humanity is one. “My understanding of oneness deepened because of the relationships with these dear friends,” says Kathryn Athay, who helped start the series of neighborhood children’s classes. “We really depend on each other and deeply care about each other.”

And on a community level, a growing nucleus of friends is continually refining how it thinks about the purpose of spiritual education, family and community. As these families serve, study and reflect day by day, they are learning what it means to be protagonists in their spiritual development and that of their community. Along the way they have been seen as developing:

- A vision of how these activities can influence transformation in society. This vision incorporates the patterns of their growth, learning objectives, postures and attitudes, interconnected systems, structures, processes and principles.

- Coherence in their efforts. They strive to stay conscious of how their thoughts and actions direct their experiences, allowing them to more effectively foster environments that strengthen unity, common purpose and prosperity.

Agreement on importance of education

This process gained traction when a children’s class got started in August 2019. Athay, reaching out to her neighbors along with fellow Baha’i Danielle Paschal, met Viji Karthik and her family, who were eager to talk about the importance of spiritual education. “My family [back in India] says that I can learn about other religions, it’s OK,” Karthik says.

Together they formed a class involving four families, with parents accompanying their children and observing the lessons.

“The children’s class is very important because children are the pillar of the next generation. The [Baha’i] classes are the root for us and we are the branches,” says Karthik, adding: “After class I sit with my son and ask him what he learned. One day he came home from class and told me, ‘Truthfulness is the foundation of all human virtues.’ This is a great example.”

As the families share their experiences, concerns and ideas, she and Athay both say, the families’ conversations and support for each other have strengthened their friendship.

“Our community makes a family,” Karthik says. “Kathryn is like my sister, we exchange our love, our light, our truthfulness towards each other.”

Athay observes that she has learned a lot about the spirit of generosity from visiting her friend’s home. “There is so much reciprocity. … The desire for spirituality, friendship and community is there.”

Greater needs, more people

Once the class had met for about three months, the people in this small nucleus of activity felt the time was right to start devotional gatherings involving neighborhood families. Viji Karthik and her husband, Karthik Bose, already kept a special prayer corner in their home, and they were happy to help their son pray and memorize short Baha’i passages.

To support this growth in activity, the need to expand the nucleus became clear. So the parents involved in the children’s class came together to consult.

They studied guidance from the Bahá’í writings about the role of parents in raising children with a world-embracing vision. They explored providing spiritual education for a growing number of children in their neighborhood, and imagined how this process could change their community.

Karthik said that consultation in January felt like “an exchange of what I know and what you know.” Paschal, who advises Baha’i communities in the area as an Auxiliary Board member, adds, “We are trying to learn how to consult about a vision, and be very upfront. It is a real transparent, beautiful, uplifting expression of the goals and the aims. Here, we were wanting to create an atmosphere and an environment that is centered around the children and their well-being.”

To help carry that vision out, they decided, more children’s class teachers should be trained. As a first step, all the parents were invited to take part in a study circle.

Using a Ruhi Institute course, Reflections on the Life of the Spirit, this space encouraged reflection, promoted the sharing of insights, and widened the scope of opportunities. It also served as an introduction to the Baha’i institute process, a global system of learning through study, service, reflection and planning.

Community building through COVID-19

Then the spread of COVID-19 interrupted the flow of activity, and the nucleus of eight friends had to think creatively to sustain momentum. In any community-building process, Paschal observes, “you get to a point … where you anticipate [that there will be a] crisis and once you do, you look at it in a different way and you embrace it.”

So in facing this disruption, “we focused on conversations with parents about each child’s progress,” says Athay. The parents were asked to reinforce their children’s understanding of spiritual qualities and spiritual concepts at home. They also agreed to move the children’s class to an online platform.

To expand participation in the children’s class, they created invitation sheets and dropped them off at neighbors’ doors.

“Perhaps this was a time when parents would be especially receptive to extra support and love for their children, as well as a time when more people would recognize the need for spiritual growth and strengthening connections and friendships in the community,” says Athay.

She and the whole nucleus were continually learning about how to invite more people into active involvement. She remembers reasoning, “I am learning so many things through this children’s class, so why don’t I see it as an opportunity to bring others into that experience with me?”

That learning process began to be shared more widely. Young people, children’s class coordinators, and emerging teachers from around the Beaverton area were invited to visit the online class, then reflect along with the teachers on their observations. Those discussions encouraged some visitors to take action in their own neighborhoods.

One visitor in April was a 15-year-old girl who had participated in a club at school whose members took Ruhi Institute courses. She started helping with the children’s class and participated in a study circle on teaching children’s classes, along with two parents from the neighborhood nucleus.

That allowed for a new Grade 1 class to be started for seven newly involved children, while the older children began Grade 2.

As classes started taking place three times a week, Athay says, “All those participating learned to exercise a high degree of flexibility. … Conversations and consultations with parents significantly increased.”

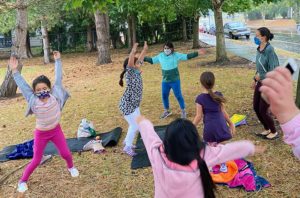

More growth emerged from there. A children’s class parent worked with Athay to develop a food-bank project for the apartment complex where they live, and Viji Karthik and other neighbors help maintain it. A class for pre-schoolers was started. A child in the Grade 2 class began hosting devotional gatherings for the families — first online, then outside with safety precautions.

In July, the parents gathered outside a middle school and consulted about paths of service they could open to keep this nucleus growing. The Bose family offered to start a devotional gathering for the whole neighborhood at a nearby park.

A second nucleus forms

And the Quiñonez family has emerged as a second nucleus of community-building activity in another pocket of the Greenway neighborhood.

Lizeth Quiñonez, 5, often sings a song she has learned with words to a Baha’i prayer: “¡Oh Dios! Guíame, protégeme, ilumina la lámpara de mi corazón y haz de mí una estrella brillante.

Tú eres el Fuerte y el Poderoso.”

Her older sister Yesi says that prayer “is inspiring to me because God is always with us.”

Athay met Lizeth and her mother, Ana, on a day parents were carrying invitations throughout the neighborhood. Members of both women’s extended families eventually became the core of a community school initiative, which Athay as a certified elementary teacher was able to organize.

The class schedule incorporates arithmetic and literacy, along with the Baha’i children’s class and a junior youth group for those of middle-school age. Yesi and a cousin help teach the children.

This second nucleus of activity also began a community library book exchange to give the children easier access to a variety of books, especially during the pandemic.

“Apart from school this is another way of learning,” says Ana Quiñonez. She became attracted to the spiritual education program “because it’s good for the children and good for us. It’s also something I had never seen before, so here we are, trying our best.”

Unexpectedly, it helped her learn better how to do videoconferencing. Some time into the pandemic, the group tried to hold classes outside, but summer wildfires reduced air quality and forced everything back indoors, “and we had to continue [the classes] through Zoom.”

“It was a difficult process but little by little I learned to use [Zoom]” with Athay’s help, she relates. When other everyday experiences required the use of this tech, “such as my children’s school or even my doctor’s appointments, I knew how to use it because I had already learned with the children’s class teacher.”

This entire experience has motivated her to keep learning more about the spiritual education process. “We will try, we will keep inviting others, so that this becomes bigger and more known and more beautiful, so that [the program’s] intentions may bear fruit. I aspire for my children to join these groups, that they may be inspired by the older youth [who serve their communities] and follow in their footsteps so that they can help children younger than themselves … and become one of the leaders, one of the teachers,” she says.

Young people’s involvement

Yesi Quiñonez, 13, helps with the online children’s classes and the new community school, as well as participating in a junior youth group. “When we work hard together it is better than working by yourself,” she says. “This [community-building] movement joins friendship and God.”

When she helps younger children, she says, “I feel like I’m encouraging others to be kind. Like when the virus wasn’t here, we used to share our food [with the neighbors]. Sharing is caring, we’re trying to teach these little kids, like my sister, to share and to be kind to others even if they aren’t kind back.”

She adds, “I learned that I like working with children a lot because I like being with them and learning with them as I teach them too, and they really seem to like it. And I also like working with my friends because they are there with me and it’s fun. We can laugh and work and learn.”

Her cousins Carla and Laura (Lala) live in the same neighborhood. “I didn’t really think that I wanted to work with kids,” says Carla, 17, but she has come to enjoy helping Athay with the classes, which include Lala, a fifth-grader.

“They really like learning about all of this. … On Monday, Yesi and I were able to teach the little ones a game. … I didn’t think I would ever be working with kids. I am now thinking of my future career, originally in business, now it is between business and education.”

The vision moving forward

Every contributor to this process is gaining the vision to pursue greater goals, Athay adds. The study circle on teaching children “has become a tool for a team of parents and teachers to collaborate in a more systematic way. Our vision continues to broaden and we have now begun discussing how we can grow from one class to three, and then to embrace 100 or more children.”

This growing nucleus of involved people continues to re-examine the way it thinks about community, Athay says. The main elements are love, mutual support, raising capacity in others, and strengthening the systems that provide them with more coherent lives.

Reflecting on this past year, Paschal sees flexibility as a hallmark. “This tool of consultation is so vital when it comes to collaboration, mutual support and friendship. When things are difficult you consult, when things are going great you consult, if things are ambiguous you consult,” she says. “You’ll need all the qualities necessary for consultation like love, detachment and being patient.”

Athay has experienced another change. “Before this whole experience, when someone would say ‘Baha’i community,’ the image that would come to mind is the people that were registered as Baha’i,” she says. “Now I picture a group of families sitting together outside my apartment complex and some are Baha’i, some are not, some are religious, some are not — but we all live here close to each other and we are all learning how to implement Baha’u’llah’s vision for humanity every day.”