A living resource: Local, national Bahá’í archives can enrich learning and lives

While the word “archives” can invoke images of vast, dimly lit storage facilities whose contents rarely see the light of day, Baha’i holdings from the past frequently enrich the lives of those in the present. Take, for example, the story of Charlotte Brittingham Dixon’s ring.

The archives of the Washington, DC, Baha’i community holds papers and several relics that belonged to Dixon, who started the city’s first Baha’i group in the late 19th Century. One of her descendants, who found her way to the Baha’i Faith after her own independent investigation, visited the DC Baha’i community to find out more about Dixon and discovered the ring.

“She was getting married,” says DC archivist Helia Ighani Hock. “And so we gifted it to her, which I thought was sweet.”

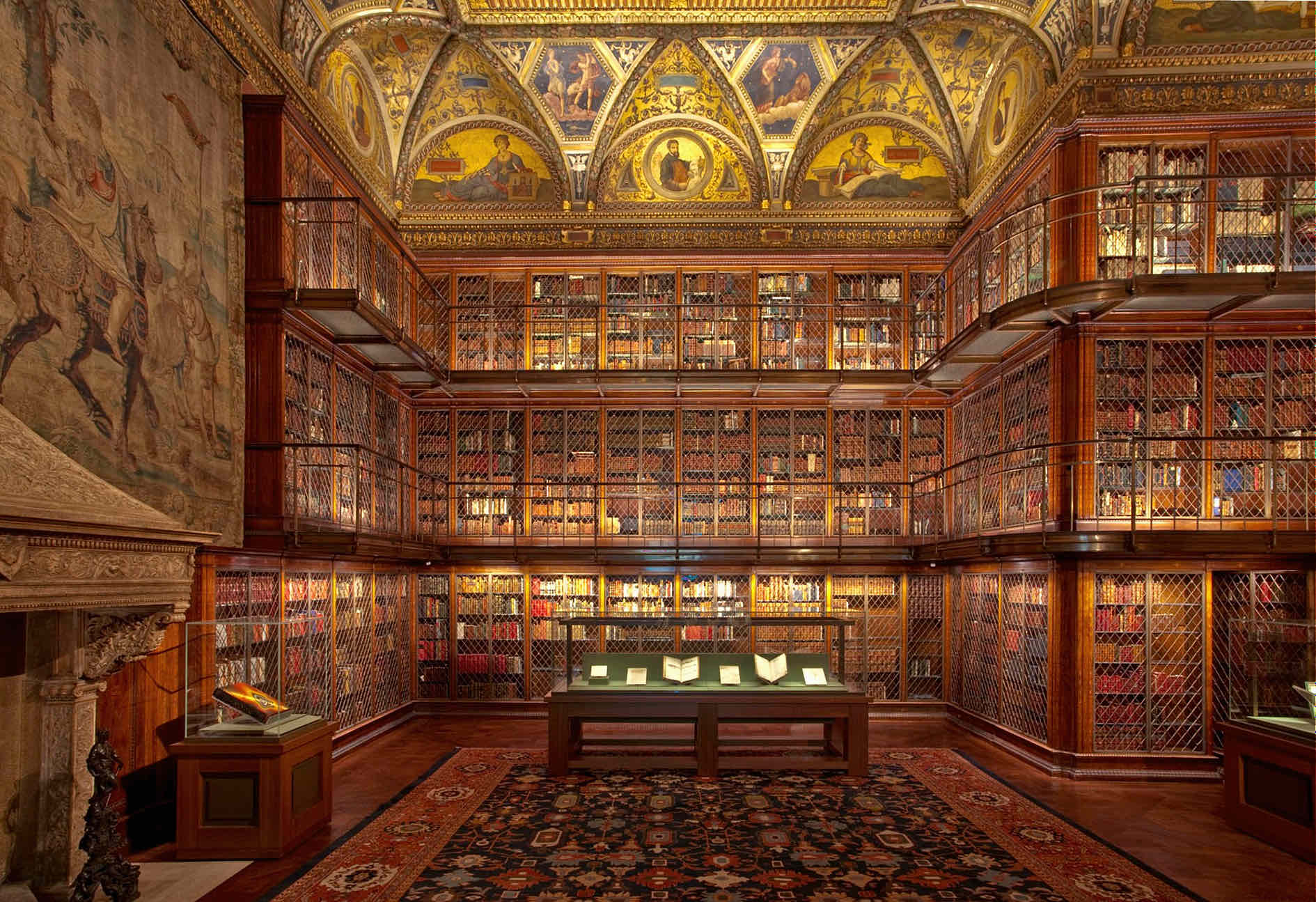

Another archival asset that recently touched present-day lives is held by the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City. The library, founded by the late 19th and early 20th century financier J.P. Morgan with the help of librarian Belle da Costa Green, was visited by ‘Abdu’l-Baha on His sojourn in the United States and Canada in 1912. ‘Abdu’l-Baha stopped at the library to meet with Morgan at the latter’s invitation, and, even though the financier could not be present because of a financial emergency, spent time perusing the collection, which included rare Persian manuscripts.

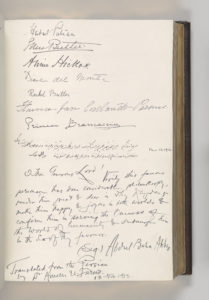

As He ended His visit, ‘Abdu’l-Baha signed the library’s guest book and left a blessing for Morgan, which was translated by those with Him: “O, Thou Generous Lord, verily this famous personage has done considerable philanthropy, render him great and dear in Thy kingdom, make him happy and joyous in both worlds, and confirm him in serving the Oneness of the World of humanity, and submerge him in the sea of Thy favors. ‘Abdu’l-Baha Abbas.”

A member of the New York City Baha’i community and a former volunteer at the library at the Baha’i World Center, Carrie Smith, found out about the inscription while searching for ways to commemorate the centenary of ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s death, which Baha’is throughout the world observed in November 2021. She went to see it and a finger-sized book of Baha’i writings also held by the library, first on her own and then, with the help of the Morgan Library staff, with eight other members of her community. The visit gave Smith and the other Baha’is a chance to talk to the library staff about the station of ‘Abdu’l-Baha and the significance of His inscription for Baha’is.

“It felt like a mini pilgrimage,” says Smith of the visit. She later invited the staff to the community events celebrating ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s life and legacy.

Another and, perhaps, the primary way that Baha’i archives breathe life into today’s community is through the books and articles of authors and researchers who use what they find in archives to reach the Baha’i community and the wider public.

Ed Sevcik, who directs the U.S. National Baha’i Archives, says such researchers find great value in its collections. They include the personal papers and effects of several hundred early Baha’is and institutions; the stored archival papers of the National Spiritual Assembly and its offices, schools, and committees; several hundred artifacts, many related to the Central Figures of the Faith; roughly 200 works of art, including paintings by abstract artist Mark Tobey; books; and voluminous amounts of audiovisual materials, which Sevcik and other archivists are in the process of digitizing. He says the material most sought after by the wider community are the papers of Robert Hayden, a Baha’i and the first Black Consultant in Poetry to the U.S. Library of Congress, a position that has since been renamed as the U.S. Poet Laureate.

Archivists are not only concerned with the past—they also spend a good deal of time acquiring, organizing, and documenting information from the present. Hock, the Washington DC archivist—in addition to archiving the community’s ongoing births, deaths, marriages, etc., and the records of the Local Spiritual Assembly—is recording stories from DC community members about the changes they have seen in the community over the course of their lives. In doing so, she is capturing their contributions to advancing the Baha’i Faith so those in the future will have a better understanding of the communities of today.

Similarly, Jan Mauras, the archivist for the New York City Baha’i community, has devoted herself to archiving the community’s efforts to better understand racism and its implications for the Baha’i and wider community.

The oneness of humanity has always been a key principle of Baha’i teachings. A core requirement is the elimination of racial prejudice and the national governing council for the Baha’i Faith in recent years has urged the community to redouble its efforts.

“The Assembly has taken on racism in a really substantial way,” Mauras says, “meeting with African American believers, finding out what their experience of being a Baha’i in New York is and what needs to be done. I think we’ve gotten much more serious about trying to understand how to address racism… And what they’re doing now all goes into the archives.”