Conversations on race, and beyond, arise from junior youth group

Parents and friends in Florida find the wish to ‘be loving humans together’ is contagious

It began as a quest to befriend fellow school parents and talk with them and their kids about forming a junior youth group.

From there, says Leah Roberts, a Baha’i in Tampa, Florida, sprang conversations on race and gatherings where the parents, their junior youths and others can “be loving humans together and talk about other life challenges.”

“It just broke my heart,” Roberts says, when her efforts to form a children’s class or junior youth group while her son Jackson, now 16, was in those age groups didn’t pan out.

Classes for the spiritual education of children and groups empowering middle school-agers to be agents of positive change in their community are two of the core activities Baha’is initiate in neighborhoods across the U.S. and the world.

So two years ago, when Mercy, now 12, entered fifth grade, Mom had a plan.

“I just started to really seek out getting to know the parents of the kids in her grade,” she recalls.

“And in trying to make friends with them, the conversation naturally went to concern for our girls. And it allowed me to bring up the concept of the junior youth group.”

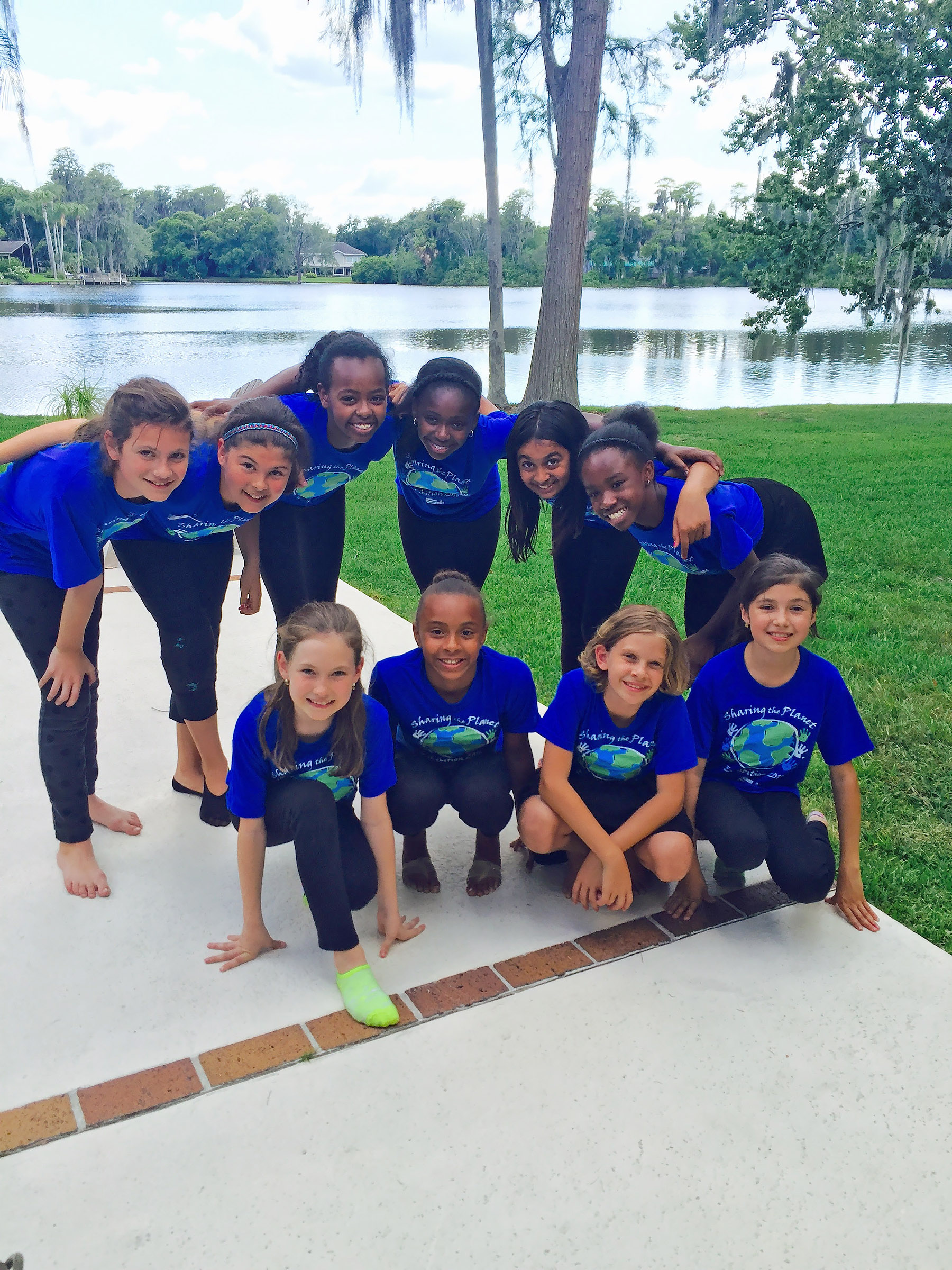

Roberts figured she had a little time to prepare; junior youth groups typically start in sixth grade. But the parents and junior youths were so enthused they prevailed upon her to start the group right away.

“Everyone wanted to be a part of it,” she says. “It was so fantastic.”

A gathering fed by years of relationship building

And as relationships deepened over the next couple of years, she says, all sorts of topics “organically and naturally” started bubbling to the surface among the diverse set of parents and junior youths.

Among those was racial injustice, fueled by stories that had begun dominating the news cycles.

“We ended up … feeling like we needed to do something,” says Roberts.

So she put out word to a large number of people of all backgrounds, via an event page on Facebook, that she and her husband, Hardy, would be hosting a conversation the next evening in their home.

All were welcome to attend and invite others to attend, she says. And they did. Eighty-five people participated, including many of the junior youth group members and their parents.

“In fact, our home filled to the point we could see the front door continue to open but we couldn’t fit any more,” she recalls.

“We don’t even know how many people were turned away. It was so full. And I would say 50 percent of the people who came we were meeting for the first time.”

The evening began with Leah and Hardy Roberts, both of whom are white, sharing a bit about the Baha’i Faith and their motivation.

“We explained that we wanted to avoid politics and foster oneness, and that as Baha’is all of our beliefs pivot around unity.”

She still marvels how “beautiful, powerful” was the conversation that ensued among “an extremely diverse group of people.

“We had the tough conversations, heartfelt, painful. And yet there was no contention.”

People stayed until midnight socializing over cake and other goodies.

An evolving focus on life challenges

A second conversation was held later with 65 people in attendance. And when media outlets got wind of the gatherings, Roberts and an African American friend sat for several interviews.

Mercy’s school also took notice, forming a diversity committee and asking Leah Roberts to be a member.

Within the junior youth group, the impact was more indirect, in her view. “For most of the families it served to solidify their participation with the group and their friendships with our family,” says Roberts.

Mention to the junior youths in August about what transpired in Charlottesville, Virginia, led to “an extremely fascinating conversation with those girls,” she says.

In the arena of public conversations, Roberts learned in talking with several people that at this point they want to address a number of topics.

Building on the race conversations, she says, “They want to … just be together and practice it while thinking about other aspects of life.

“They want to get together and be loving humans together and talk about other life challenges. I think that is moving. To have them somehow be part of all that and just watch that process is incredible.”